CEREMONIAL LIFE

To this day, ceremonies play an important part in Aboriginal life. Small ceremonies, or rituals, are still practised in some remote parts of Australia, such as in Arnhem Land and Central Australia, in order to ensure a supply of plant and animal foods. These take the form of chanting, singing, dancing or ritual action to invoke the Ancestral Beings to ensure a good supply of food or rain.

The most important ceremonies are connected with the initiation of boys and girls into adulthood. Such ceremonies sometimes last for weeks, with nightly singing and dancing, story telling, and the display of body decoration and ceremonial objects. During these ceremonies, the songs and stories connected to each of the Ancestral Beings are told and retold, some being “open” for women and children to see and hear, others being restricted or “secret-sacred”, only for the initiates to learn.

Funeral ceremonies. Another important time for ceremonies is on the death of a person, when people often paint themselves white, cut their bodies to show remorse for the loss of their loved one, and conduct a series of rituals, songs and dances to ensure the person’s spirit leaves the area and returns to its birth place, from where it can later be reborn.

Burial practices vary throughout Australia, people being buried in parts of southern and central Australia, but having quite a different burial in the north. Across much of northern Australia, a person’s burial has two stages, each accompanied by ritual and ceremony.

The primary burial is when the corpse is laid out on an elevated wooden platform, covered in leaves and branches, and left several months for the flesh to rot away from the bones. The secondary burial is when the bones are collected from the platform, painted with red ochre, and then dispersed in different ways. Sometimes a relative will carry a portion of the bones with them for a year or more. Sometimes they are wrapped in paperbark and deposited in a cave shelter, where they are left to disintegrate with time. In parts of Arnhem Land the bones are placed into a large hollow log and left at a designated area of bushland. The hollow log is a dead tree trunk which has been naturally hollowed out by the action of termites.

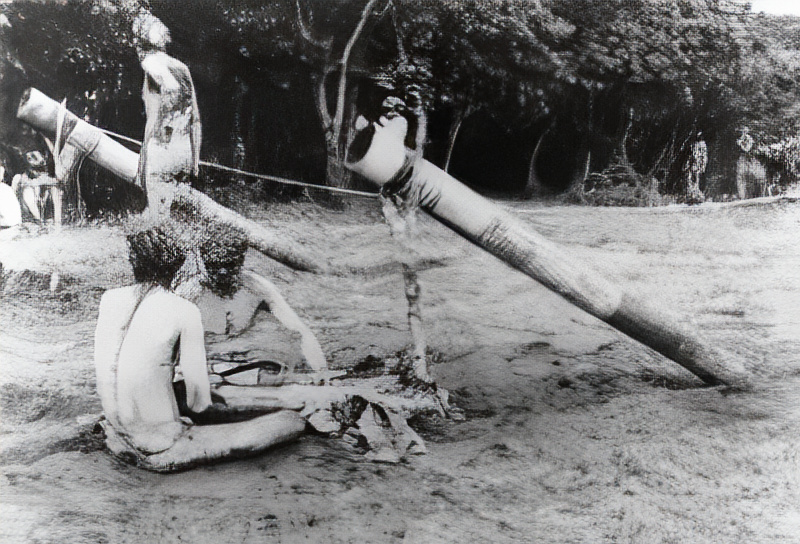

Aboriginal rock art records ceremonies and dances, practised to this day, which date back tens of thousands of years. At the right, a man dances a pose with his arms outstretched, holding a short stick in each hand. The photograph was taken in Darwin, possibly in the 1920s.

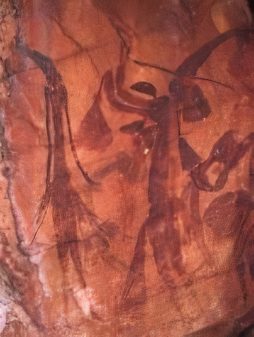

The same pose, with a person holding short sticks in outstretched hands, was painted in a Kimberley (north Western Australia) rock shelter by an early artist.

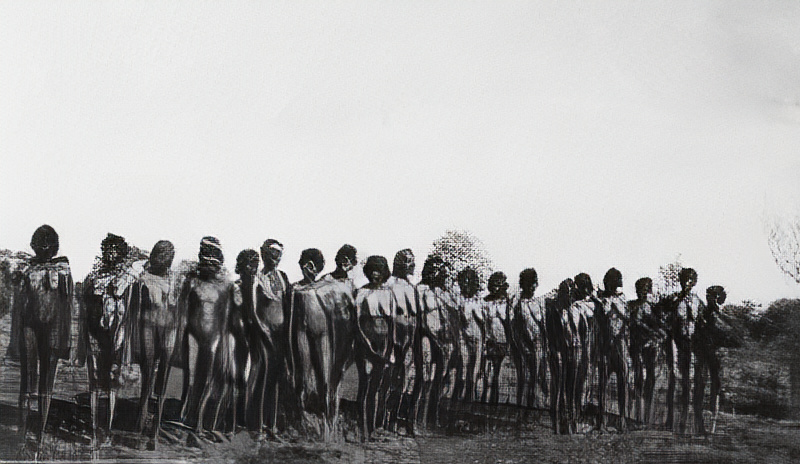

Conical and “bucket” headdresses are worn during a public performance ceremony in Alice Springs. Two boomerangs are used as clap sticks to beat time for the singing. The conical headdress and knees bent in a dancing pose appear in the early rock art of the Kimberley.